Women and Medicine

in the Middle Ages and Renaissance

Medicine Before and around 1600

Medical care before 1600 involved a wide variety of tactics: 'holistic' lifestyle prescriptions and diets based on the theory of humors; direct applications of various substances alone or in combination; bloodletting, cauterization and cupping; use of holy relics and prayers as well as other ritual/magical actions; and prayers to saints, charity, pilgrimages and other 'acts of virtue'. Herbs, spices, resins, stones and other substances were used in drinks, pills, washes, baths, rubs, poultices, purges, enemas, suppositories, pessaries, bandages, ointments and most other conceivable forms to treat illness. A wide variety of practitioners were also involved-- university trained physicians, literate and illiterate 'empirics', religious, surgeons, barbers, apothecaries, midwives, relatives of the patient and specialist healers of one type or another.

Medicine's view of Women

Eve and Medicine (and Aristotle)

The learned schools of medicine subjected women to a double whammy of medical contempt: not only were there church doctrines about the inferiority of women due to Eve, but many Greek and subsequent ancient writers, such as Aristotle, wrote misogynist texts about women and their bodies.

In most schools of thought, women were held to be weaker, more prone to vices, including sexual vices, humorally more cold and damp, and generally inferior copies of the male organism. Church doctrine was that the discomfort, pain and peril of childbearing were women's lot because of the sins of Eve.

Because learned medicine concentrated almost exclusively on theory and rehashing of classical texts, there was room for writings by male monks and scholars who had no practical experience of women or women's medicine. The most outstanding would be the 'Secretis Mulierum' by the pseudo-Albertus Magnus, which is chock full of horrible distortions and misinformation.

Because medieval Western Europe was a 'birth-positive' culture which placed a high value on human reproduction, women's roles in childbearing were very important to the culture. There was heavy emphasis on conceiving and bearing children, and men blamed women for any infertility. On the other hand, there was a positive side to childbearing, as seen in traditions such as the celebratory post-partum visits and special clothes and furnishings for the mother in Renaissance Italy.

Menstruation

Menstruation was of grave concern to classical, medieval and Renaissance medical writers and physicians. Modern anthropologists have noted that excessive concern with menstruation is a characteristic of many birth-positive cultures. Not only did regular menstruation indicate fertility, but by the theory of humors, women's excess humors and buildup of bodily wastes were flushed by regular monthly courses. If these did not occur, the wastes would build up and cause illness. An older woman who no longer menstruated posed a serious safety concern since the excess humors and wastes were thought to be able to poison men and sometimes children and others with whom she came into contact.

Conception & Birth

Male writers often had trouble with the basic anatomy of the gynecological parts. Though some had a very good idea of how the parts subject to manual examination were formed, there were arguments about the number of chambers in the uterus and other matters of anatomy.

Though some authorities still believed that male semen was the only engenderer of the child, most agreed that the child was equally formed and nourished from the male semen and female menstrual fluids that were retained during pregnancy. In general, it was considered necessary that both the man and the woman be fully satisfied during intercourse for conception to occur (which was good for married women but bad for rape victims).

Fertility was a major concern. In one well recorded case, a italian woman seeking to become pregnant was offered a multitude of advice. Her physician offered humoral theory. Her sister found both a female empiric who would produce a plaster to apply on the abdomen and another specialist that would produce a blessed girdle. Her brother-in-law suggested acts of charity and prayer.

Sources on 'Women's medicine' available to period people:

- De Secretes Mulierium, a nasty text that Christine de Pisan condemned as 'full of lies'

- The texts making up the Trotula-- one on ob/gyn, one on ob/gyn and cosmetics, one on cosmetics

- The Seeknesse of Women, an extract from the works of Gilbertus Anglicus

- Some of the writings of Hildegarde of Bingen, notably Physica and Causa et Curia

Medical Treatments for women

Some historians claim that "Women's medicine is women's business". Others provide plenty of evidence that women medical practitioners treated men, and men treated women even in gynecology and obstetrics (though a female intermediary would be employed for manual examinations).

General Gynecology

Treatments (or at least home remedies) for itching, burning, vermin and whites (yeast infection) were included in many texts. Other types of illness, such as breast cancer and uterine cancer were known, though treatments for them were rare and dangerous. Women who were celibate could incur various discomforts, to be abated by applications of warm oils to the genitalia and poultices to the abdomen. Surgery for cancers and fistulas was not unknown, though a dangerous procedure. Various treatments for bladder disorders were also prescribed.

Menstruation

Menstruation indicated fertility, and the concern for regular menstruation led to a number of remedies 'to bring down women's courses' which may or may not have been abortifacient. However, most of the items specified as causing menstruation have little or no abortifacient potential. Women who did not menstruate might suffer from wandering of the uterus; a misplaced uterus could cause pain in other parts of the body, and even cause stoppage of breath. 'Suffocation of the uterus' due to lack of menstruation was treated in various ways, with drinks, steam-baths, and manual manipulation. For young women, treatments for disorders of menstruation generally included the suggestion of marriage and sexual intercourse.

Conception

Europe in the middle ages was what is referred to as a 'birth-positive' culture. That is, they valued reproduction above other considerations. Many rules, medical treatments and stratagems are suggested in the documents for encouraging conception, especially conception of a healthy child, preferably a boy. For instance, having pictures of boys and handsome men about during pregnancy, and avoiding all distressing sights, were recommended by physicians and writers.

While strategies to prevent conception were forbidden by the church, by common law and by the society, it does seem that some sort of conception regulation was practiced in some cases -- both the Trotula and the Secrets of Women describe contraceptives. Furthermore, population analyses suggest that births may have been limited by choice in some way.

Pregnancy & Childbirth

Though the care of women during pregnancy does not appear to be exclusively controlled by other women, women figured prominently there. During the pregnancy, though, women might well consult male physicians for a variety of advice, and university physicians and literate male doctors had access to texts that show a variety of obstetrical presentations. Some women (such as the queen of Jaume II of Spain) were attended in childbed by male physicians, but midwives or maids were employed to do any manual examination.

Many texts suggest not only health regimens for the pregnant woman but also remedies for the various discomforts of pregnancy, such as swollen feet and painful breasts.

The best documentation about childbirth and aftercare seems to be provided by illustrations on wooden trays and majolica ware made to be used by the new mother in Renaissance Italy. (Jacqueline Musacchio describes and depicts in detail these presentations and their social setting.)

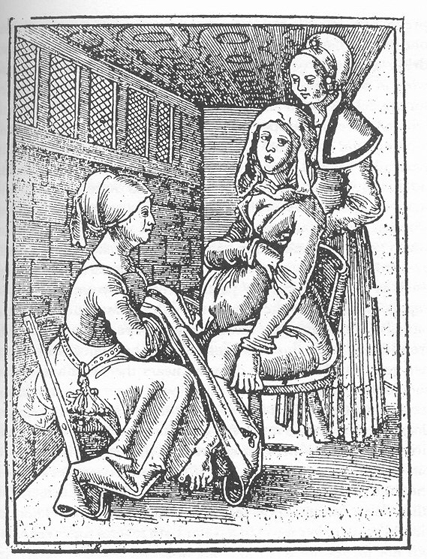

Childbirth: Woodcut from Der Swangern Frawen und he bammen roszgarten, by Eucharius Rösslin, 1513. (Arons, 1994)

Illustrations depict women usually giving birth in some kind of chair, sometimes using a birthing stool that was v-shaped to support the legs while giving space for the midwife to work; however illustrations also suggest that x-shaped chairs and other normal sorts of chairs were used, as well as the half lying position and a crouching position.

Birthing Chair: Woodcut from Der Swangern Frawen und he bammen roszgarten, by Eucharius Rösslin, 1513. (Arons, 1994):

Birthing Chair: Woodcut from Der Swangern Frawen und he bammen roszgarten, by Eucharius Rösslin, 1513. (Arons, 1994):

...She should lie down on her back, but she should not lie down completely and yet also she also should not quite be standing, but rather it should be somewhere in the middle . . . And in high German lands, and also in Italian lands the midwives have special chairs for a woman's labor, and these are not high, but carved out and hollow on the inside, as depicted here. And these should be made so the woman can lean back on her back . . . And if she is fat, she should not sit, rather she should lie on her belly, and lay her forehead on the ground and pull her knees to her belly . . . (Arons, 1994)

Anointing the belly and the vulva, especially the perineum, with oils and unguents was practiced to help reduce tearing. (Medical books specify instructions for repairing torn perineum with stitches.)

Prolapsed uterus and hemorrhaging were common complications, as were difficult presentations, such as buttocks-first. Retained placentas and dead children retained in the womb were also a concern. There are many remedies suggested for expelling the dead child from the womb; some of these could have been used as abortifacents.

Intentional abortion, though illegal, was known, though the substances and procedures doctors and priests reported as being used were generally dangerous and/or ineffective.

Lactation (breastfeeding)

By the latter part of our period, it was common for women of the upper and upper middle classes to send their children out to wetnurses. It's not clear from the documents why this was so fashionable, but there is likely to be one important factor: women who were not breastfeeding were likely to conceive sooner.

[In Russian and some Eastern orthodox church areas, the wetnurse was a necessity, since no-one, including the child, could eat in the presence of a postpartum woman until she had completed the 40 days purification and been 'churched'. How this was arranged is unclear but prominent women used wetnurses.]

As a result, some women needed help stopping their flow of milk, while others needed to encourage it. There are a variety of medicaments and botanicals recommended in the herbals and texts to encourage or discourage lactation; also certain activities and diet were said to affect lactation.

On the other hand, by the end of the period many medical and advice texts strongly recommend that women nurse their own children instead of resorting to wetnurses.

In addition, most herbals and other kinds of texts prescribe remedies for 'sore breasts' without specifically mentioning lactation: these may have been connected with lactation or the symptoms of dysmenorrhea.

Children's medicine

With the high level of infant mortality, women faced an uphill battle in raising their children even to the age of 5. Infectious diseases, injuries, and even unrecognized birth defects could kill. In at least one case, women medical personnel were directed to treat only women and children (Valencia). Accounts of miracles and sometimes household accounts indicate that physicians were consulted for children. However, there does not seem to have been a specific discipline of pediatrics.

Place of Women in Medicine

Inside the Home-- Dr. Mom.

It is generally assumed by modern historians and by the writers of many manuscript sources that the wife, mother, lady of the house, or female head of the household, was responsible for first-line and in most cases all medical treatment in the home.

While this practice is not as strongly documented in earlier records, by the sixteenth and early seventeenth century it is explicitly stated by authors such as Thomas Tusser (500 points of good husbandry) and Gervase Markham (The English Housewife). Earlier, we see writers condemning women practicing on their families (for instance, Chaucer's story about Chanticleer, where his wife nearly poisons him with her suggested remedies).

In farm and manorial households, the owner's wife was expected to provide medical care not only to her own family but to servants and dependents, including tenants and neighbors of lower status. If she did not provide the care herself, she was responsible for seeing that it was done. In Le Menagier de Paris (written in the late 1300s), the husband instructs his wife to drop everything and see to the care of any servant fallen ill. "The charities of the Roman noblewoman Francesca Bussi dei Ponziani (St. Francesca Romana, 1384-1440) included doctoring not only the members of her wealthy husband's large household but also neighbors, friends and strangers in need." (Siriasi)

Most people in the middle ages appear to have had a basic understanding of the prevailing medical theory of the day, that of humors; and women and men would have been familiar with a variety of treatments for illnesses and injuries. (What we would now call a combination of first aid and folk medicine.) For bleeding, cauterization and cupping, a specialist might be called in, as well as for surgeon's work (such as cutting for the stone or removing cataracts). Physicians might be consulted on a trip to the city. In larger households, a household physician might be on salary and thus take the place of the lady in prescribing physic (though actual care was probably delegated to family members and/or female servants).

Margaret Paston's husband's comments on her medical knowledge survive in the Paston letters. Queen Isolt, from the Tristam saga, is both a sorceress and skilled physician, and ladies of the castle who turn out to be 'skilled physicians' show up with great regularity in the romances.

However, Monica Green has pointed out that we cannot prove that women had access to medical, much less gynecological texts, on a regular basis, any more than men did. They seem to have instead used their increasing literacy toward the end of period to assemble collections of 'receipts' in their own handwriting for various medicaments (and cookery!)

Outside the home

The myths that all women's medical care was provided by midwives, or that all female medical practitioners were midwives, has been widely challenged. Green, and others, have made a strong case that small numbers of women are documented to have occupied almost all the ranks of medical personnel of the middle ages. Furthermore, women were not universally restricted to treating 'women's diseases' or even women.

Siriasi has this to say:

"Women as well as men practiced medicine and surgery; as with their predecessors in the Roman empire, women's practice was limited neither to obstetrical cases nor to female patients. For example, the names of 24 women described as surgeons in Naples between 1273 and 1410 are known, and references have been found to 15 women practitioners, most of them Jewish and none described as midwives, in Frankfurt between 1387 and 1497...

Even in the twelfth century, however, the accomplishments of Trota and Abbess Hildegard were highly unusual. Once university faculties of medicine were established in the course of the thirteenth century, women were excluded from advanced medical education and, as a consequence, from the most prestigious and potentially lucrative variety of practice. Furthermore, it deserves to be emphasized that although women practitioners existed in many different regions of Europe between the thirteenth and the fifteenth centuries, they represent only a very small proportion of the total number of practitioners whose names are recorded-- according to one estimate, about 1.5 percent in France and 1.2 percent in England. It is probably that many more women may have engaged in midwifery and healing arts without leaving any trace of their activities in written records; but this in turn may imply that such women are likely to have clustered in the least prosperous sector of medical activity, or to have been part-time or intermittent practitioners." -- Siriasi, p. 27

Women Physicians

Only a small number of women were treated as 'physicians' in period. Partly this was because, after the founding of medical schools in universities, physicians were expected to attend university schools of medicine-- and women were generally not welcome in universities.

Dame Trota, a possibly apocryphal figure, is the most famous of the women university physicians. It is said that she practiced at the University of Salerno, along with a number of other female medical scholars referred to as 'the Salernitarian Women'. A number of writings have been attributed to Trota, specifically those gathered together in the collections referred to as the _Trotula_.

Some historians claimed that all the texts in question were written by men and merely attributed to Trota; however, another extant general medical work by Trota was identified by John Benson. Monica Green advances a compelling argument that at least one of the Trotula texts was in fact written by a woman physician, though perhaps not Trota herself.

Some women were licensed as doctors or medical professionals in various states, and various writers have claimed that a few women attended medical school in period. In cases where women healers were licensed, the historians perceive a blurring between the status of physicians and licensed healers. For instance, in Naples, and in Florence, and even in Valencia (before 1329) women could be licensed as 'medica' during certain historical periods.

'Empirics'

The term 'empiric' was used by university trained physicians to refer to non-university trained medical practitioners, especially those who were illiterate and learned their skills by practical training.

Empirics could be general healers/doctors or specialists, and their level of knowledge and ability to cure varied widely. Some of the lower-status healers also resorted to prayers, charms and even attempts at magic to supplement their cures.

Both men and women practiced as empirics, and as the power of the university physicians grew, both men and women empirics were forced out of the trade. However, because of their inability to attend universities, as well as the prejudices of male physicians and lawmakers, women were especially targeted by this sort of campaign.

Surgeons/barbers

Because surgeons and barber-surgeons were often organized into guilds, they could hold out longer against the pressures of licensure. Like other guilds, a number of the barber-surgeon guilds are recorded as allowing the daughters and wives of their members to take up membership in the guild. An example is "Katherine la surgiene of London, daughter of Thomas the surgeon and sister of William the Surgeon" in 1286 (Rawcliffe) Widows of members were generally allowed to retain their husbands' status in the guild if they so chose, at least until they remarried. The guilds of Lincoln, Norwich, Dublin and York appear to have accepted female members until quite late in period. Even in London, "The London Surgeon Nicholas Bradmore held his apprentice Agnes Woodcock, in such high regard that he left her a red belt with a silver buckle and 6s. 8d. in his will of 1417, although she may, ironically have been one of the last of her sex to receive formal training in the City." (Rawcliffe)

The records, according to Rawcliffe, indicate that women were often eye surgeons, because of the delicacy required for the work. Some of the "Women of Salerno" are considered to have been surgeons.

Apothecaries

Diligent searches of the historical records have turned up a small number of female apothecaries recorded in Western Europe, generally daughters, wives or widows of apothecary guildmembers.

Midwives

Midwives, those who helped the parturient mother to give birth and provided a limited amount of before and after care, were exclusively women. Women in labor may not always have been attended by midwives; sometimes accounts give no information about midwives being present at a birth or paid for a confinement. Women might be attended by their female relatives, friends, or servants during birth; and since having experience given birth oneself was a major qualification for midwives, that might make recourse to a midwife considered unnecessary.

The medical expertise of the midwife could vary widely. Midwives were generally taught via practical training and/or their own childbirths-- by 1600, in London, an apprenticeship system was in place where younger midwives served 7 years under an older midwife. In the upper classes, a midwife might be supervised during the delivery by the patients' female relatives, or even, in rare cases, by the father or a male physician-- but records and depictions suggest that men generally did not enter the confinement room, except in severe cases.

It was expected that in really severe cases--- such as when the mother was dying and a cesarean operation needed to be performed to retrieve and baptize the infant-- the midwife would refer the case to a physician.

Midwives were not infrequently prosecuted in church courts for providing charms either to assist the mother in childbirth or pregnancy, or to encourage conception. Such practices made them more vulnerable to persecution during the witch craze. However, before 1400, such practices, if overtly Christian, superstitious or 'magical' behavior were dealt with less harshly. Robin Briggs, in Witches and Neighbors, asserts that midwives were generally not persecuted as witches.

Nurses

There were a number of hospitals set up as charitable foundations in the Middle Ages, and they generally employed women nurses, sometimes with the status of servants, other times as 'lay sisters'. The immense amount of work expected of these nurses has been detailed by several authorities, as they fed, washed, dressed, cared for the sick, did the laundry, cooked the food, and washed, laid out, and shrouded the dead.

Minkowski, on the nurses at the Hotel-Dieu in Paris: "Nurses arose at 5:00 am, attended chapel prayers after ablutions, , and then began work on the wards. Their duties included using a single portable basin to wash the hands and faces of all patients, dispensing liquids, comforting the sick, making beds, and serving meals twice daily. Sisters on night duty reported at 7:00 pm. It was their task, in an era before the bedpan, to conduct the ill to a communal privy, for which purpose the hospital provided a cloak and slippers for every two patients."

If the hospital had a ward for pregnant women or took in orphans, they cared for children as well. (Though hospitals tried to send foundlings out to wet-nurses, if such could not be found, the staff had to feed the infants with cloths dipped in milk.) These hospitals generally turned away those with infectious diseases and had little in the way of strenuous treatment regimes: usually they performed the functions of nursing home and hospice for the poor who sought refuge there. Relatively clean surroundings and nourishing food, as well as the occasional apothecary dose, was the standard of care.

Women sometimes held responsible positions in these hospitals, but not all the time. Minkowski reports that in German hospitals, women often held the posts of Custorin (similar to a steward), Meisterin (head of the kitchens), and Schauerin (implementing hospital admission policies). In orphanages, Minkowski reports, "the Findelmutter was the healer for these children."

Sources:

- Barkai, Ron. A history of Jewish gynaecological texts in the Middle Ages. (Brill, 1998)

- Baron, J.H. "The hospital of Santa Maria della Scala, Siena, 1090-1990." British Medical Journal, Dec 22, 1990 v301 n6766 p1449(3)

- Barratt, Alexandra. The knowing of woman's kind in childing : a Middle English version of material derived from the Trotula and other sources. (European Schoolbooks, 2001

- Bell, Rudolph. How to Do It: Guides to Good Living for Renaissance Italians. Univ. of Chicago, 1999.

- The book of women's love : and Jewish medieval medical literature on women : sefer ahavat nashim. edited and translated with a commentary by Carmen Caballero-Navas. (Kegan Paul, 2004)

- Bowers, Rick. Thomas Phaer and the Boke of Chyldren (1544). (Mrts, 1999).

- Briggs, Robin. Witches & Neighbors: The Social and Cultural Context of European Witchcraft.(Penguin USA, 1998)

- Brown, Judith, and Robert Davis. Gender and Society in Renaissance Italy. (Longman, 1998)

- Bullough, Vern and James Brundage, eds. Handbook of medieval sexuality. (Garland, 2000)

- Cellier, Elizabeth (Dormer). To Dr.---- an answer to his queries, concerning the College of Midwives, 1688 [computer file] : Women Writers Project first electronic edition. Subscription service: http://www.wwp.brown.edu/texts/cellier.todoctor.html

- Dangler, Jean. Mediating Fictions: literature, women healers, and the go-between in medieval and early modern Iberia. Bucknell University Press, 2001.

- de Cuerla, Domingo. "Public record of the labour of Isabel de la Cavalleria, January 10, 1490, Zaragoza" Translated by Montserrat Cabre. Edited by Maria del Carmen Garcia Herrero, Las mujeres en Zaragoza en el siglo XV. (Zaragoza: Ayuntamiento de Zaragoza, 1990), vol.II, pp.293-295; previosly published by the same author in Homenaje al Profesor Emerito Antonio Ubieto Arteta. (Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza, 1989), pp.290-292. Previously online in the Online Reference Book for Medieval Studies: http://www.the-orb.net/birthrecord.html

- Ehrenreich, Barbara and Deirdre English. Witches, midwives, and nurses : a history of women healers. (Old Westbury, N.Y. : Feminist Press, 1973)NOT RECOMMENDED.

- Ferraris, Zoë and Victor. "The Women of Salerno: Contribution to the Origins of Surgery From Medieval Italy," The Annals of Thoracic Surger, Volume 64, Issue 6, December 1997, p 1855-1857.

- Fildes, Valerie A. Breasts, bottles and babies: A history of infant feeding. (Edinburgh University Press, 1986)

- Furst, Lillian. Women healers and physicians: climbing a long hill (University Press of Kentucky, 1997)

- Getz, Faye. Medicine in the English Middle Ages, (Princeton University Press, 1998)

-

Green, Monica. ‘Documenting Medieval Women’s Medical Practice,’ in Practical Medicine from Salerno to the Black Death, Ed. Luis García-Ballester, et al. (Cambridge University Press, 1994).

- Green, Monica. Making Women's Medicine Masculine : The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology. (Oxford University Press, 2008)

- Green, Monica H., and Daniel Lord Smail. “The Trial of Floreta d’Ays (1403): Jews, Christians, and Obstetrics in Later Medieval Marseille.” Journal of Medieval History 34, no. 2 (June 2008): 185–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmedhist.2008.03.001.

- Green, Monica. The Trotula : a medieval compendium of women's medicine. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001)

- Green, Monica. Women's Healthcare in the Medieval West: Texts and Contexts. (Ashgate, 2000).

- Green, Monica, "Women's Medical Practice and Health Care in Medieval Europe," Signs Vol. 14, Iss. 2 (Winter 1989); p. 434-74.

- Hallaert, M. The "Sekenesse of wymmen" : a Middle English treatise on diseases in women (Yale Medical Library, Ms. 47 fols. 60r-71v).

- Hayes, Dawn Marie. "Pregnancy and Childbirth in Anglo-Saxon England." http://www.medievalmaternity.org/anglosaxon/index.htm

- Hildegarde of Bingen. Hildegard von Bingen's Physica: the complete English translation of her classic work on Health and Healing. Trans. from the Latin by Patricia Throop. ( Healing Arts, 1998).

- Hildegarde of Bingen. Holistic Healing (Causa et Curiae). (Liturgical Press, 1994)

- Hughes, Muriel Joy. Women healers in medieval life and literature. (Books for Libraries Press, 1968)

- Hunter, Lynette and Sarah Hutton, eds. Women, science and medicine, 1500-1700: mothers and sisters of the Royal Society. (Sutton, 1997)

-

LaBarge, Margaret Wade. A Small Sound of the Trumpet : Women in Medieval Life. Beacon Press, 1986.

- Lascaratos, J., D. Lazaris and G. Kreatsas. "A tragic case of complicated labour in early Byzantium," European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, Volume 105, Issue 1, 10 October 2002, Pages 80-83

- Lemay, Helen R. Women's Secrets: A Translation of Pseudo-Albertus Magnus's De Secretis Mulierum with Commentaries. (State University of New York Press, 1992)

- Maclean, Ian. The Renaissance notion of woman : a study in the fortunes of scholasticism and medical science in European intellectual life. (Cambridge University Press, 1980)

- "MEDICINE AND MEDIEVAL WOMEN." Women in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2004. Also available in Credo Reference.

- Medieval woman's guide to health : the first English gynecological handbook / with introd., transcription of the Middle English text, and modern English translation by Beryl Rowland. (Kent State University Press, c1981)

- Minkowski, William L. "Women Healers of the Middle Ages: Selected Aspects of Their History." Journal of Public Health, Vol. 82, no. 2 (February 1992): p. 288-295

- Musacchio, Jacqueline M. The Art and Ritual of Childbirth in Renaissance Italy. (Yale University Press, 1999)

- Nissen, Alanna. “Transgression, Pollution, Deformity, Bewitchment: Menstruation and Supernatural Threat in Late Medieval and Early Modern England, 1250 - 1750.” M.A., SUNY Empire State College, 2017.

- Purkiss, Diane. The witch in history : early modern and twentieth-century representations. (Routledge, 1996. )

- Rawcliffe, Carole. "Hospital Nurses and their Work", in Richard Britnell, ed. Daily Life in the Late Middle Ages, (Sutton Publishing, 1998), pp 58-61.

- Rawcliffe, Carole. Medicine and Society in Later Medieval England. (Sutton, 1995)

- Riddle, John. Contraception and abortion from the ancient world to the Renaissance. (Harvard University Press, 1992)

-

Rodríguez Suárez, Jesennia. “Menstruation as a Primary Concern in the Ideas of Naḥmanides.” EHumanista/IVITRA 13 (2018): 394–403.

- Roper, Lyndal. "Witchcraft and Fantasy in Early Modern Germany," in Lorna Hudson, ed., Feminism and Renaissance Studies. (Oxford University Press, 1999)

- Rösslin, Eucharius. When Midwifery became the Male Physician's Province: the sixteenth century handbook The Rose Garden for Pregnant Women and Midwives [Der Swangern Frawen und he bammen roszgarten] newly Englished. Translated by Wendy Arons. (McFarland, 1994)

- Rowland, Beryl, trans. Medieval Woman’s Guide to Health : The First English Gynecological Handbook. Kent State University Press, c1981

- Scragg, D. G., Audrey Meaney, Anthony Davies, Anthony, Peter Kitson, and S. J. Parker. Superstition and popular medicine in Anglo-Saxon England (Manchester Centre for Anglo-Saxon Studies, 1989)

- Sharp, Jane. The Midwives Book or, The whole art of midwifry discovered : directing childbearing women how to behave themselves in their conception, breeding, bearing, and nursing of children in six books, 1671. Women Writers Project first electronic edition. http://www.wwp.brown.edu/

- Siraisi, Nancy. Medieval & early Renaissance medicine : an introduction to knowledge and practice.

- Van De Walle, Etienne, and Elisha Renne, editors. Regulating Menstruation: Beliefs, Practices, Interpretations. (University of Chicago Press, 2001)

- Whaley, Leigh Ann. Women and the Practice of Medical Care in Early Modern Europe, 1400-1800. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

-

“Medicine and Medieval Women.” Women in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2004.

Copyright Jennifer A. Heise. 2003-2018. Contact me via email for permission to reprint: jenne.heise@gmail.com

Permission is explicitly granted for limited reproduction as a printed handout for classes in schools, herb society meetings, or classes or guild meetings in the Society for Creative Anachronism as long as I am notified and credited and the entire handout is used.

Jadwiga's herbs homepage: http://www.zajaczkowa.com/jadwiga/handouts

Birthing Chair: Woodcut from Der Swangern Frawen und he bammen roszgarten, by Eucharius Rösslin, 1513. (Arons, 1994):

Birthing Chair: Woodcut from Der Swangern Frawen und he bammen roszgarten, by Eucharius Rösslin, 1513. (Arons, 1994):